Child Sacrifice in Gehenna

If you have not yet read my blog post on the background context of Gehenna, I would highly suggest you read that first before this post so that this post would make sense. It contains a substantial amount of background context to the Hinnom Valley and is crucial to understanding the concept of hell first. It is located HERE.

To Molek or As a Molk?

Child sacrifice is a subject matter that many Christians are unaware of but has nevertheless produced severe disputes in the sphere of scholarship. The crux of the argument is that when the Bible speaks about making sacrifices to Molek, the Scriptural witness references a foreign deity to which the Jews made sacrifices. However, in 1935, a scholar named Otto Eissfeldt published a short book suggesting that as an alternative to reading to Molek in the Hebrew Bible, a better reading would be as a molk which denotes a type of sacrifice offered–not a specific deity. That potential translation significantly impacts Biblical interpretation because that version would presume the molk sacrifice would therefore be offered to Yahweh and not to a pagan deity. Not surprisingly, that theory sent shockwaves through the scholarly community for several reasons. This blog looks at that debate and considers its legitimacy and what the proper interpretation perhaps might be.

Sacrifices to Molek

The Hebrew Bible mentions in various canonical books the god Molek (or Molech), which derives from the consonants from the Hebrew word Melek (“king”) with the vowels from boshet meaning (“shame”). The latter is a variant reading of the Canaanite god Baal meaning (“Lord”). The Hebrew language, however, does not use vowels so the reading would simply look like mlk, which needs to be interpreted depending on context because there are multiple possibilities as to what mlk suggests because different vowels can alter the sense of the word. Nevertheless, the conventional understanding of mlk is that it indicates Molek and is correlated with the pagan ritual of child sacrifice that was performed explicitly in the Valley of Hinnom during the reigns of Manasseh and Ahaz as depicted in 2 Kings.

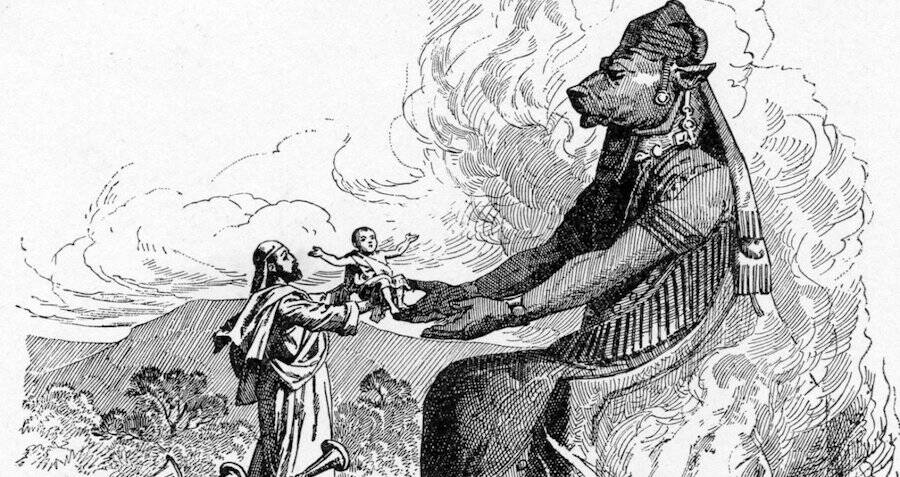

There is a wide array of artwork surrounding Molek and the occurrence of child sacrifice that displays the Canaanite god in the sitting position, with the body of a human, and the head of a bull, with his arms, stretched out to receive an offering. The priest (or parent) would then place the child in the outstretched arms and light a fire near Molek’s feet. The fire essentially burns the child to death until it becomes a pile of ashes in the arms of Molek. Some commentators maintain that drums were involved in the ritual, so the music may drown out the child screaming. Inscriptions support that hypothesis in Phoenicia that explicitly refer to music during the ceremony. However, no hard evidence is available to demonstrate that actually happened in Israel. Obviously, with a heinous activity such as this, it is considered an abomination in the Bible for the Jews to participate in this type of ritual. However, many have speculated, was this type of sacrifice an actual, historical reality that was performed in Israel?

To Molek

The common understanding of Molek worship from Scripture is that the people of Israel (and a few kings) participated in this type of sacrifice for various reasons. They are said to worship the god Molek and perform the child sacrifice by burning them alive in the Hinnom Valley. For example, 2 Kings 16:3 records Ahaz, “He even burned his son as an offering.” Several versions have “He even made his son pass through fire.” It is generally assumed this is an expression to proclaim that he sacrificed his son to Molek in fire. Likewise, 2 Kings 21:6 asserts that Manasseh participated in the identical practice as Ahaz did before him.

This abhorrent ritual is likewise condemned in Leviticus 20:2 when God declares, “Say to the Israelites: ‘Any Israelite or any foreigner residing in Israel who sacrifices any of his children to Molek is to be put to death. The members of the community are to stone him.” With a passage of condemnation of death for anyone who participates in this appalling deed written down in Leviticus, it appears that child sacrifice is an infamous practice in the ancient near east that happens to have been practiced in Israel, even if for a brief amount of time. Child sacrifice is understandably forbidden in Israel even though it is observed in certain surrounding cultures, such as Phoenicia and Canaan.

Josiah’s Reforms

Scripture documents how this practice was eventually vanquished by the great king Josiah after discovering the Book of the Law during his temple reforms. Because of this discovery, Josiah reinstitutes the Law of Moses and subsequently tears down the high places and the Asherah poles, which leads to the worship of foreign gods. Scripture then recounts about Josiah, “He desecrated Topheth, which was in the Valley of Ben Hinnom, so no one could use it to sacrifice their son or daughter in the fire to Molek.” One aspect of his temple reforms prohibited all pagan worship and reinstituted the law God gave Moses and ensured no one could sacrifice their children to Molek again.

This practice of child sacrifice was so abhorrent to God that Jeremiah records God informing him, “They built high places for Baal in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to sacrifice their sons and daughters to Molek, though I never commanded—nor did it enter my mind—that they should do such a detestable thing and so make Judah sin.” That is an obvious and understandable proclamation from Yahweh and one that defends His character from ever being associated with the act of child sacrifice. However, that begs the question, why would God feel it necessary to defend His character and respond with “though I never commanded—nor did it enter my mind,” if it genuinely was worship to a foreign god? Indeed, Yahweh would never command such a thing. He would certainly never think about commanding child sacrifice. Therefore, why does God feel it necessary to defend Himself from ever imposing child sacrifice if it specifically concerns worship to a foreign god?

As a Molk Offering

One explanation for that dilemma rests with the phrase to Molek because there is an alternative reading that appears to suit the context and language quite well. For example, since the Hebrew language did not employ a vowel system, the phrase would read lm mlk which is generally translated as lam molek, meaning for Molek. Part of the dispute rests in the Hebrew preposition le (לְ־). This word can indicate to, for, and of. When paired with mlk, it is generally assumed to mean to Molek. However, le can also mean as in English and render the exact phrase as a molk. That reading is entirely reasonable because we know from history and archaeology that a molk is a type of sacrifice present in surrounding cultures to Israel in the 7th-8th centuries BCE, frequently in the Phoenician area.

That makes the above verse from Jeremiah more apparent to understand if it is recognized as a molk offering. Therefore, when the prophet writes, “They built high places for Baal in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to sacrifice their sons and daughters as a molk sacrifice,” it appears more evident as to what the accurate meaning may in fact be. In the previous reading, they built high places for Baal (a god), so the people could sacrifice their children to Molek? High places are a place of worship and if they built high places to Baal, then why would they sacrifice to a different god, such as Molek? Likewise, the molk sacrifices from other Israelites would also be to YHWH. As a result, the reading of as a molk offering appears as if it is the correct interpretation here based on the context of the passage because they built the high places for Baal and not for Molek.

What is a Molk Sacrifice?

A molk offering is a Phoenician (or Canaanite) sacrifice when the firstborn is offered as a molk sacrifice to a god, usually Baal, and always by fire. Though it should be noted, oftentimes, an animal may be substituted for a human child. However, a human child would be seen as a “higher” form of offering. Whatever was sacrificed as a molk offering (child or animal) was burnt up much the same as a Biblical burnt offering in the old covenant. In this case, the parent would sacrifice their firstborn as a molk offering because that is the most significant and most valuable offering they can conceivably provide. As such, there are many references throughout the Hebrew Bible to this practice of offering a firstborn, by fire, in dedication to a god. The significance of this alternative reading, however, is that the child being sacrificed is not to Molek but to Yahweh. That has a profound impact on how one reads and interprets the mlk texts because the individuals were not worshipping another god but worshipping Yahweh through the sacrifice of their children.

The Biblical Timeline

Of all the contentious topics in the Bible, one of the more controversial may be the chronology of the Old Testament. Many who adhere to the conservative position think Moses wrote the entirety of the Pentateuch by himself, while the Deuterocanonical books were then composed afterward, representing most of Israel’s subsequent history. However, the vast majority of scholars today (even a few conservatives) do not believe that to be the case. Though I do not desire to get into that particular controversy here, suffice to say that I favor the majority position of scholars who advocate a Documentary Hypothesis composition, roughly in the Persian period, following the Babylonian captivity. That established chronology of composition of the OT books of the Hebrew Bible indicates an easier and more accurate method of understanding the concept of child sacrifice in ancient Israel. On the other hand, trying to fit the theory of child sacrifice into Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch proves problematic for various reasons.

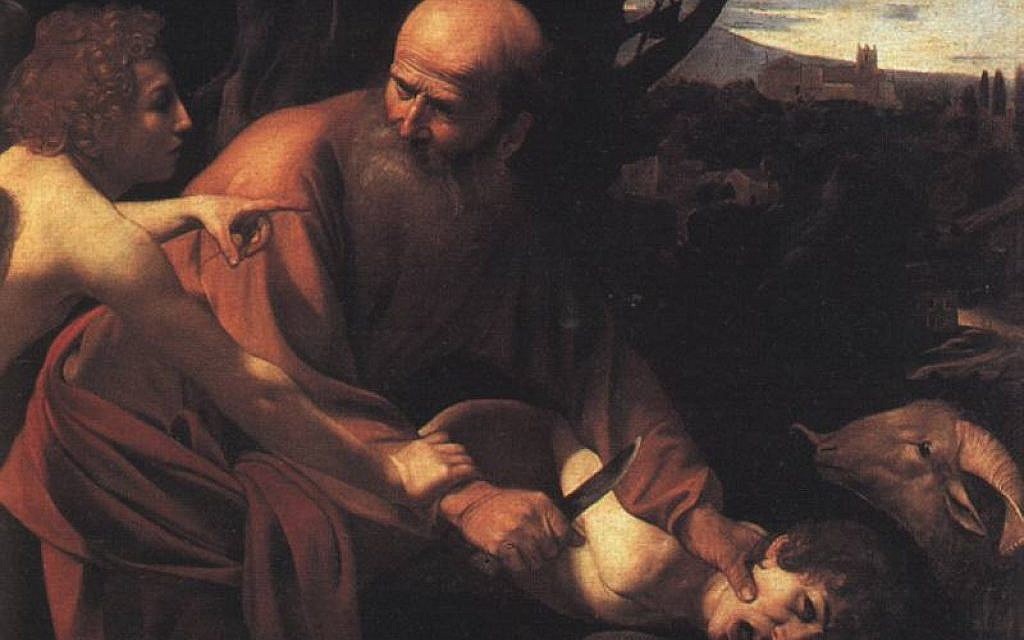

Abraham and Isaac

The famous story of Abraham offering Isaac as a sacrifice is perhaps the most familiar child sacrifice narrative in the Bible. In that story, Abraham is instructed to offer whatever is most important and most significant to Yahweh—his firstborn child. Abraham brings wood to construct a fire but is prohibited from carrying out the sacrifice, and a ram is substituted instead. This tale can undoubtedly be considered an apparent allusion to a molk sacrifice. Additionally, it can likewise be understood as a polemic against offering children as a molk sacrifice by operating in a manner to explain to an illiterate society, in narrative form, what Yahweh desires, which is not child sacrifice. Most scholars date Genesis to the period of the exile, which would fit an argument in opposition to child sacrifice well. It also demonstrates that God desires Israel to be separate from adjacent societies at the time (like Canaan and Phoenicia) who did participate in child sacrifice.

Micah 6:7

Likewise, the verse in Micah 6:7 appears to reference a molk offering when the prophet declares, “Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, with ten thousand rivers of olive oil? Shall I offer my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?” The intriguing characteristic of this passage is the reference to rams (present in the Abraham and Isaac sacrifice story) and then his firstborn, which is a molk sacrifice. This passage was written in the Judean country around the 7th-8th century BCE, which is precisely when archaeologists begin to see attestations of child sacrifices among the Phoenicians.

Jephthah

There is also the notorious story in Judges 11-12 of Jephthah who makes a rash pledge when he declares, “And Jephthah made a vow to the Lord: “If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering.” Everybody knows this story and knows that his only child (naturally his firstborn) is what comes out to meet him. Interestingly enough, Jephthah tells God he will make a sacrifice “as a burnt offering.”

This aligns well with precisely what a molk offering is and establishes that this narrative could likewise be a demonstration concerning the horrors of child sacrifice. The story of Jephthah’s daughter could also be perceived as a parable of sorts to reveal the problems of both child sacrifice and making a rash vow which aligns with the second commandment of not taking the Lord’s name in vain (swearing a pledge to Yahweh). This does not have to be a historically literal narrative to have a polemical effect on the story’s contemporary reader. Most scholars date this book around the 6th century BCE, precisely the chronology that functions with a controversial ideology against child sacrifice.

What is the Point?

Many would inquire, what is the point of knowing the difference between the two types of potential sacrifices? Notably, not too much. However, the sacrifices that we read about conducted in the Hinnom Valley were not of Israelites sacrificing to a foreign god but Israelites offering their own children to Yahweh, which makes the sacrifices in the valley that much more heinous. Sure, any type of child sacrifice is inherently evil, but to offer one’s child by fire to the God of the Bible has such a negative connotation attached to it for an Israelite that it indicates wickedness of enormous proportions occurred in that valley. Jews, who worshipped Yahweh, would kill and sacrifice their own children by fire as an offering to God in the Valley of Hinnom.

This is the valley that Jesus referenced in the Gospels when He speaks of Gehenna. This is the valley He warns the disciples about and the valley He threatens the Pharisees with. Having children sacrificed to Yahweh in the Hinnom Valley leaves such a lasting, hideous impression on the minds of the Israelites that to have any reference, of any kind, to that valley is repugnant, to say the least.

Collectivist Culture

One of the reasons this is such a major concern to an Israelite is that they are a collectivist culture, as opposed to a modern, individualistic one. That implies they care much more about their kin, family, relatives, and the overall concern and treatment of the community at large rather than simply on the individual. To appreciate that, at one point in time, their own people burned their children to Yahweh would leave them sick to their stomach. The concept and awareness of this evil act is instantly associated with the Hinnom Valley and, therefore, is considered as the single, most despised place on earth.

Hence, the biblical language in Isaiah 66:24 is all the more pertinent to the Israelite in Jesus’s day when the prophet records God saying about His enemies, “And they will go out and look on the dead bodies of those who rebelled against me; the worms that eat them will not die, the fire that burns them will not be quenched, and they will be loathsome to all mankind.” Jesus then connects this exact verse from Isaiah with His own declaration when he proclaims in the Gospel of Mark, “And if your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and be thrown into the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna), where ‘the worms that eat them do not die, and the fire is not quenched.’”

Jesus’s Statement of the Valley of Hinnom

Jesus explicitly associates the Valley of Hinnom with Isaiah 66:24 to exhibit the perils of sin. He noticeably speaks in hyperbolic language here, but the overall logic of His message is conveyed nevertheless: “Cut off the root of whatever it is that causes you to sin because that’s so much better than having your entire body thrown in the extremely shameful Valley of Hinnom, like in the days of old when parents burned their kids alive in that exact same place.” That means something to a first-century Israelite. It is a statement so significant and so profound that the original meaning is ostensibly lost on virtually all contemporary Christians due to its association to the cultural context of what transpired in the Valley of Hinnom. That statement from Jesus would undoubtedly make the disciples’ proverbial jaws drop to the floor when they heard it.

Conclusion

Realizing the full, detailed, and unadulterated history of the Valley of Hinnom should make one’s eyes open a bit more to the contextual word association that Jesus employs when speaking to the disciples and Pharisees. If Gehenna did suggest a literal underworld of everlasting torment, then why did He never tell anyone besides the disciples and Pharisees? How come no disciples subsequently went and cautioned other people? Why is there a complete lack of references to the Hinnom Valley in any of the disciples (less James) writings? The Gospels are saturated with cultural context so much that if we do not properly comprehend what is occurring in the discourses between Jesus and anyone, then we run the risk of completely misunderstanding Christ’s message.

What are your thoughts on this topic? Does it make a difference what type of sacrifice is made? Does knowing what happened in the Hinnom Valley change at all what you think about Gehenna?

Previous blog post on the OT Valley of Hinnom is found HERE

Further Reading:

Heath D. Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel (University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns), 2017.

Papaioannou, Kim. The Geography of Hell in the Teachings of Jesus. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2013.