The Ancient Persian Afterlife

Introduction

Zoroastrianism is a complicated religion to comprehend because it contains many nuances that are challenging to untangle (as there are in many other ancient religions). However, unlike Christianity, Zoroastrianism is not well attested to in ancient manuscripts. As such, the topic of hell in Zoroastrian religious thought is problematic to conclusively draw definitive conclusions from because of this lack of documentation. Therefore, this post will simply be an overview of the Zoroastrian hell and is not intended to be a completely exhaustive post of what the entire religion believes concerning punishment in the afterlife because a thorough and comprehensive treatment such as that would require at least a 200-page book.

That is not to say that we know nothing about this ancient Persian religion. In fact, we understand a considerable amount of Zoroastrian thought and what that religion believed about hell. Though admittedly not great in number, we do have some ancient textual witnesses to Zoroastrian teaching. Regrettably, many of those are generally considered a later composition, and, as such, the earlier material that was composed may have been quite different from what we possess today. As a result, much of what is written concerning this ancient Iranian religion may not be precisely what it looked like in the first and second millennium BCE when it originated, but ought to be at least somewhat comparable.

What we do know

One aspect of the religion that Zoroastrian scholars are seemingly in unison with is that there was indeed a prophet named Zoroaster (a Greek version of his real name, Zarathustra). Still, we know almost nothing about him or even when he lived. Though, most scholars would now speculate a Bronze-age date (1200 BCE) for the prophet, while others may think a date closer to the sixth century BCE. Additionally, many Zoroastrian scholars accredit at least some of the writings in the sacred text (called the Avesta) to the prophet himself, though no one can be absolutely certain. Whether Zoroaster wrote the actual words or not, many would at least presume that some of those teachings derived from the prophet himself.

The Bible of Zoroaster—The Avesta

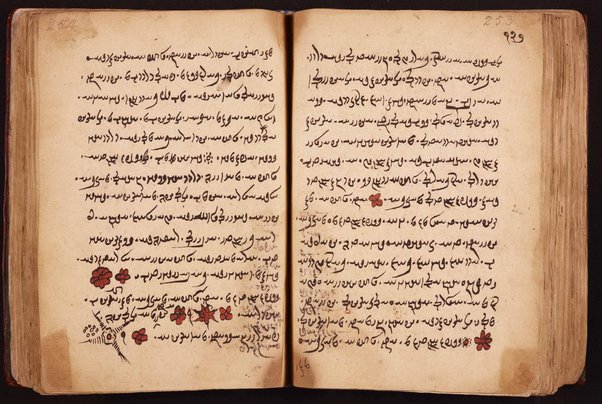

The Avesta, the primary (and most likely oldest) sacred religious text of Zoroastrianism, is comprised predominantly of hymns and teachings assembled in Gathas (similar to how Psalms and Proverbs are in the Hebrew Bible). Unlike the Bible, though, there are very few narratives within the Avesta, with most of the text basically focusing on worship and liturgical practices, along with hymns, poems, as well as a few teachings.

Overall, there are a total of 17 hymns within 5 Gathas, which are all typically attributed to Zoroaster himself. Concerning the topic of hell, there is little material within this early sacred text that discusses explicitly what occurs to the wicked after death. Most of what we know about hell in Zoroastrianism comes from secondary texts generally dated anywhere from the 6th to 9th century CE (though, admittedly, they could be drawn from earlier sources). These later Zoroastrian texts that are not present in the Avesta would be similar to the writings of Christianity’s early church fathers or even some of the NT apocryphal texts that further describe and clarify theological ideas that are not contained (or perhaps unclear) within the Bible. As a result, both Christianity and Zoroastrianism require further details concerning their main religious text from subsequent explanatory texts.

Dualism in Zoroastrianism

One of the main characteristics, and a chief identifier of the religion of Zoroastrianism, is its dualistic nature. Unlike most all of the ancient religions before it, there is no pantheon of gods with different titles and roles for each independent deity. Instead, Zoroastrianism is a monotheistic religion with one true god—Ahura Mazda (“Wise Lord”), who was the creator of the heavens and the earth and will defeat evil once and for all in his own time by overcoming the devil-like entity Ahriman (“Evil One” or “Lord of Lies”). Ahriman (viewed as the contrasting spirit of the good Ahura Mazda) dwells in the darkness of hell under the earth and sends his demons to torment the world and punish those in the afterlife. Though many religions now adhere to something similar, Zoroastrianism was perhaps the first ancient religion to observe what is now recognized as dualism.

Zoroastrianism Hell

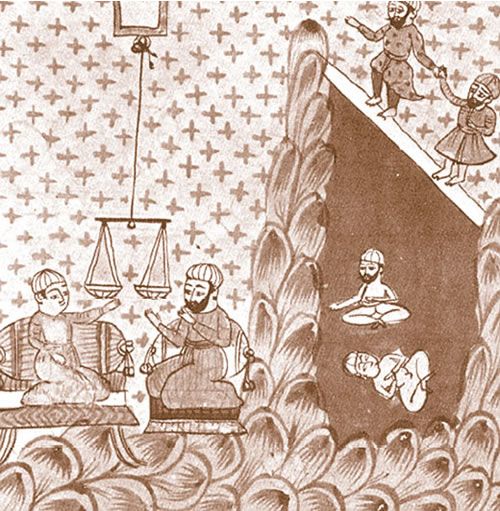

Unlike Christianity, the devil in Zoroastrianism is the one who presides over hell and performs the punishments and torments that befall the souls consigned to the underworld. The Zoroastrian hell is similar to the Egyptian Duat (more information on that can be found HERE) in that a person’s soul is weighed and evaluated by a judge and then a sentence is imposed on the individual. The judge that decides what happens to a soul after death is named Rashnu, who is considered similar to a genie or even an angel of justice. The determining factor in what happens to an individual concerning their eventual fate in the afterlife is according to how the soul succeeds or fails during the judging process corresponding to the total amount of their good or wicked deeds in life.

If the soul’s good deeds outweigh the evil, a beautiful woman called Daena would accompany the soul, along with two guardian dogs, across a bridge called the Chinvat bridge that led into the “House of Song,” which is comparable to our modern version of Heaven. This bridge is viewed in the Zoroastrian religion as the “bridge between life and death.” It is representative of one’s soul that crosses over from this present and physical life to the spiritual afterlife. If the person’s soul is judged worthy, then the bridge is wide and easy to cross, leading the individual into the House of Song. However, if the individual’s soul is judged not good, then the bridge is razor thin and easy to fall off, which forces the individual into hell, which is known as the Duzakh (literally “bad existence”).

Hell in Religious Texts

The Duzakh is not explicitly revealed in the older, sacred text of the Avesta, except regarding the story above about the Chinvat bridge and judgment. We have some writings of a 3rd-century CE Zoroastrian priest named Kirdēr who supposedly witnesses hell while he is walking by the Chinvat bridge. As he passes by it, he looks down into the pit and observes the experiences of individual souls in hell. It should be noted, however, that while the priest perceives what is happening in hell, there are no written descriptions in his writing as to precisely what those punishments are. As a result of this story being in the 3rd century CE, ultimately bridging the gap between the older Avesta and subsequent later religious texts, many Zoroastrian scholars can confidently say that hell had a reasonable history by this time, though it was not fully established yet. It therefore appears probable that the Duzakh was known in some capacity and almost certainly taught in some manner prior to the 3rd century and possibly may coincide with the teachings during the time of Christ.

The Arda Viraf

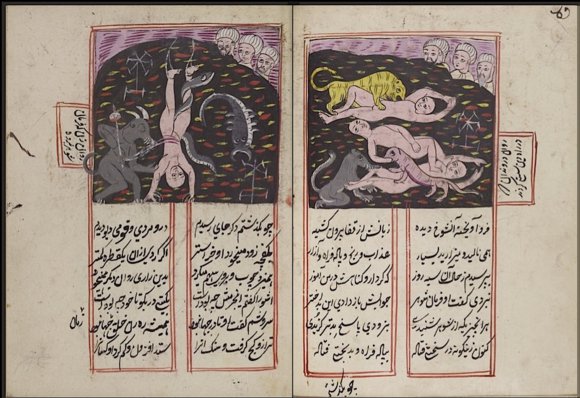

However, it is not until a later account known as the Arda Viraf that we see a detailed description of the torments of hell in Zoroastrianism. The Arda Viraf is one that rivals (and even surpasses) Dante’s Inferno and later Christian apocalypses like Apocalypse of Peter in regard to its punishments. In this Zoroastrian story of hell, named after the main character, and possible author, Arda Viraf, the seer is taken on a journey of the Duzakh by two guides—Srosh the pious and Ataro the Angel (spelling alterations of these two guides are numerous due to a large number of variations among manuscripts. This blog follows the spelling and pronunciation in Eileen Gardner’s book Zoroastrian Hell). The Arda Viraf consists of 101 chapters, with 85 of those chapters recounting the author’s observations of hell and its torments, with 79 chapters being in a highly structured question-and-answer format.

The Arda Viraf is a well-organized and poetic work that illustrates much about the afterlife along with both Heaven and hell. The piece about hell (which is the largest of the work) follows a relatively rigid and repetitive arrangement that consists of Arda Viraf witnessing a soul in torment and then asking the two guides why this soul was in torment and what his/her sin was that led them into hell, and more importantly, the specific punishment they are experiencing. The narrative begins in the first three sections by describing a river in which souls must attempt to cross with the aid of their guardian angels. If friends and relatives, however, shed too many tears, the river swells and grows, effectively preventing the dead from successfully crossing the river.

Punishments in the Duzakh

After the initial explanation of the river, Arda Viraf comes upon the Chinvat Bridge to witness a wicked soul who has just died. The deceased’s disembodied soul has been sitting at the head of his physical body for three days. Afterwards, the soul then sees a grotesque, ugly, decayed naked woman approaching him. The wicked soul then asks what this female spirit is doing, and she replies, “I am your bad actions, O youth of evil thoughts, of evil words, of evil deeds, of evil religion. It is on account of your will and actions that I am as hideous and vile, iniquitous, and diseased, rotten and foul-smelling, unfortunate and distressed, as I seem to you.” This female spirit is the bodily reflection of the wicked soul’s evil deeds while on earth and now provides a reflective look into the soul’s actions while he/she was alive.

After the introduction to the river, the Chinvat Bridge, and the wicked soul, the story of Arda Viraf then follows a cyclical question-and-answer format with the seer and the two guides that continues in that structure for 85 total visions. An excellent example of this structure is as follows:

I also saw the soul of a man, the skin of whose head they continually flay, and with a cruel death they perpetually kill him.

And I asked, “What sin was committed by this body, whose soul suffers such a punishment?”

Srosh the pious and Ataro the angel said, “This is the soul of that wicked man who, in the world, slew a pious man.” (Chapter 21)

That question-and-answer formula is then repeated numerous times over, with many being so grotesque and cruel that it is not even appropriate for this blog. In fact, there was even a translation of the Arda Viraf in a book called Sacred Books of the East, where author and translator E.W. West broke off translation by saying, “From here onward the pictures of the tortured souls become too nauseous to follow.” If you are interested in reading the Arda Viraf, you can find the link HERE. Scroll down to “Part 4. Hell.”

Other Writings Containing Hell

Though the Arda Viraf is perhaps the most well-known Zoroastrian text in relation to the topic of punishment in the afterlife, there are a few other writings in the Zoroastrian religion that likewise discuss hell. For example, in a 6th Century CE text called A Book of Scriptures (Hadhokht Nask), there is a conversation between Ahura Mazda (the good God) and the prophet Zoroaster in which they discuss the fate of the soul during the first three nights of death when the soul sits at the head of the dead body (mentioned above). Towards the end, Zoroaster asks, “When a wicked man dies, where does his soul dwell that night?” Then, after a small exposition between God and the prophet on what the soul does on the first three nights of death, Ahura Mazda speaks about the 4th and final night and proclaims, “On the fourth, the soul of the wicked man advanced with a footstep into the eternal gloom.”

A few other minor texts concern hell in Zoroastrianism, but these aforementioned tales are the main writings in which we can catch a glimpse into the ancient Persian religion and how they viewed and taught punishment after death for the wicked. A good resource is a short 49-page book on Amazon from scholar Eileen Gardner called Zoroastrian Hell: Visions, Tours, and Descriptions of the Infernal Otherworld. A link to the book is HERE.

Fire in Zoroastrianism

Though hell is described in Zoroastrianism with various forms of punishments, including burning and melting, fire is never explicitly mentioned as punishment. That is because the Persian religion saw fire as part of worship and a symbol of purity maintained in fire temples called Agiaries. The fire represents God (Ahura Mazda), as well as the “illuminated mind” in humans. In fact, fire is so revered in Zoroastrianism no ceremony is performed without it. That is a common motif for how most other ancient civilizations perceived fire as being representative of the supernatural and/or divine. As a result, the fires in Zoroastrianism are said to never be extinguished because of how holy it is considered to be and therefore, ought not to be utilized for punishment.

There is, however, a writing called the Bundahisn that describes how fire (personified as a divine agent), in cooperation with the evil Ahriman, will melt all the metals in the hills and mountains, causing the molten metal to flow over the entire earth. All individuals must pass through this flood of metal-infused lava eventually. For the righteous, it will be a pleasant experience similar to a refining or purifying encounter. Though, for the wicked, it will feel like physically walking through molten metal and what that would feel like to the senses should it actually transpire. However, at the eschatological transfiguration of the world, this molten metal will eventually purify and release all sinners from hell, and then hell itself will be purified by the same molten metal. Ultimately, the fire is responsible for the eventual purification of all individuals and the destruction of hell itself. So, while many of the previous “hell texts” in Zoroastrianism discuss eternal punishment, there are other later writings which describe a variety of universal reconciliation similar to Christian Universalism.

Did Zoroastrianism influence Christianity?

Though there does appear to be quite a few similarities between the ancient Persian religion and Christianity, the link between the two is challenging to demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt, particularly concerning the concept of hell. Since most all Zoroastrian scholars postulate a 6th-9th century CE date of the primary religious texts that speak of hell, the influence may actually be from Christianity to Zoroastrianism. Oxford professor Robert Charles Zaehner (1913-1974) claims that the similarities and historical context between the two religions and the thoughts about hell are so relevant that “it would be carrying skepticism altogether too far to refuse to draw the obvious conclusion.” The only problem now is, which way does the influence go?

Many appear to think that Zoroastrianism influenced Christianity, and while that may be true to some extent, the concept of hell may, in fact, be the other way around. For example, it appears evident that the description and nature of hell in the Arda Viraf mirrors the 2nd century CE Christian writing The Apocalypse of Peter rather closely (a translation can be found HERE)

For example, in the Apocalypse of Peter (AoP), Peter is taken on a journey of hell and witnesses the torments of sinners who are there, much like what is written about the journey in the Arda Viraf. However, instead of two guides explaining what is happening to the sinners, it is Jesus himself who explains to Peter what is transpiring. For example, one passage from AoP is eerily similar to what is found in the Arda Viraf when the author of the Christian apocalypse writes

And beside them that are there, shall be other men and women, gnawing their tongues; and they (demons) shall torment them with red-hot iron and burn their eyes. These are they that slander and doubt of my righteousness. Other men and women whose works were done in deceitfulness shall have their lips cut off, and fire enter into their mouth and their entrails. These are the false witnesses (all these are they that caused the martyrs to die by their lying).

Compare that to chapter 29 in the Arda Viraf:

I also saw the soul of a man whose tongue hung out of his jaw and was ever gnawed by khrafstars (demons). And I asked, “What sin was committed by this body, whose soul suffers such a punishment?” Srosh the pious and Ataro the angel said, “This is the soul of that man who, in the world, committed slander and embroiled people one with one another, and his soul, in the end, fled to hell.”

There are a few others that appear to be very close resemblances of sins and punishments that are contained in both texts. Since we can confidently date AoP to the 2nd century CE and the Arda Viraf to at least the 6th century CE (if not much later), it appears that if there is an influence of hell on one another, it is much more likely that Christianity influenced the Zoroastrian version of hell.

Conclusion

Hell in Zoroastrianism appears to be much similar to what modern individuals think “hell” ought to be like, with its never-ending torments and punishments that last for eternity at the hands of the devil and his demons. Though there are several Zoroastrian texts which address the topic of hell, none of them appear in the beginning stages of the Persian religion. Much like how the concept of hell in Christianity (and earlier Judaism) was not around at the beginning of their respective faith, Zoroastrianism’s eternal punishments show up later than the original sacred texts contained in the older Avesta. It is therefore ill-advised to conclude that Christianity derived its concept of hell from Zoroastrianism due to its later composition in the Persian religion. However, the influences and similarities concerning the doctrine of hell should not be disregarded but should rather be observed with how and why they mirror each other in several distinct ways. This would provide a good look into how the doctrine of hell evolved over time and over diverse religions.

Next blog post on the history of hell is the Greek underworld Hades found HERE.

Previous post on the Egyptian underworld, the Duat, is found HERE

Sources for further reading:

Eileen Gardner, Zoroastrian Hell: Visions, Tours and Descriptions of the Infernal Otherworld

Alan Bernstein, The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian World

http://www.avesta.org/mp/viraf.html

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arda-wiraz-wiraz

https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2013/12/zoroastrian-visions-of-heaven-and-hell.html