Honorable and Shameful Deaths

Introduction

A first glance, Jewish views of death and burial appear to not be in relation to the topic of hell. However, understanding the consequence and manner of death as described in the Hinnom Valley (Gehenna) does have a direct correlation with the “hell” passages in the New Testament. Therefore, this post will examine the ancient Jewish view of death and how those views influence Jesus’s Gehenna accounts in the Gospels.

Good and Bad Death

In ancient Israel, the manner in which someone dies is considered either a good or bad death. Good death would consist of dying in old age, dying in peace, martyrdom, and being buried with your family, just to name a few. Examples of a bad death would be a death that is premature, violent, shameful, leaving no heirs, being cremated, or not receiving a proper burial. In an honor and shame culture like Israel was, the manner in which you died would remain with your name and, therefore, categorize the deceased in either an honorable or shameful fashion. That is a significant concept that should not go unnoticed when reading the Hebrew Bible.

Jewish Views of Death

Ancient Israelites responded to death as both something to fear and something to be welcomed, depending upon the conditions surrounding the manner of one’s death. As portrayed in Scripture, the way someone died indicates a great deal about what the author is attempting to say concerning the individual. For example, Genesis records Abraham’s death as: “Abraham breathed his last and died in a good old age, an old man and full of years, and was gathered to his people” (Gen 25:7).

The insinuation is that Abraham lived a respectable and moral life and is rewarded with a death from God that brings honor to his name. These words read much like a funeral speech when the deceased is being honored in front of friends and family. Again, in Israel’s honor and shame culture, that is considered one of the noblest ways a person can die. Similar stories of honorable deaths from the Hebrew Bible would be Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, and Joshua, to name a few.

Bad Death

On the contrary, a bad death is something to be avoided at all costs. For instance, in the story about Saul’s death, the king knows this cultural aspect of what a shameful death entails because he requests his servant to kill him by his own sword so that he may not die at the hand of his enemies. When his servant refused, Saul fell on the sword himself and ended his own life. Suicide is not common in the Bible, but in this instance, it is perceived as a more honorable method of death than at the hands of an enemy—particularly for a king.

An example of one of the numerous bad deaths documented in the Bible is Sisera, the general of the Canaanite army in the book of Judges. After his defeat in battle, he escapes and happens upon a woman named Jael, who provides him shelter. While sleeping, Jael drives a tent peg into his temple “until it went down into the ground.” Being killed in this manner is considered an extremely shameful way to die, especially in this culture. However, Sisera being killed in this manner and by a woman is all the more dishonorable. The Bible records countless ways in which a person dies. By focusing on the Biblical description of one’s death, the reader can get an excellent sense of what the author is attempting to suggest concerning how they died.

Burial Law

Without a doubt, the most common criterion for having a good death is proper burial. This is frequently achieved by being buried in one’s own cave (or a family’s cave), which is the standard means of interment for a Jew. Being buried in this manner and following a period of mourning by close friends and family members, the deceased will be remembered in a respectable fashion, which brings honor to not only their name, but their family’s name as well. Anytime burial (or non-burial) is mentioned in the pages of the Bible, the author is attempting to reveal something about the individual. It is good to observe precisely what the author of Scripture says about how a biblical character died because there may be additional, unspoken information being communicated than what is explicitly written.

For an individual to experience a good death, it is vital for a proper burial to be performed, which is typically within 24 hours after death (Deut. 21:23). Some of the reasons for this have to do with the climate in Israel. However, it is primarily because of how ceremonial unclean a dead body is considered to be. Therefore, a burial ought to transpire somewhat quickly after death. The mourning process then commences and can continue for a period of seven days. It is then maintained after the sealing of the tomb for a total of thirty days of mourning. It was an exceptionally unique ritual in ancient Judaism to mourn for the deceased because it demonstrates the importance of loved ones and how much they are missed. Conversely, if an individual were not mourned, it was implied in that culture that they were viewed perhaps as shameful or the near the bottom of the social landscape.

Isaiah 66:24

To emphasize precisely how shameful ancient Judaism believed non-burial to be, the final verse in Isaiah serves as a demonstration of what society thinks of having one’s corpse exposed and left out in the open. This verse states, “And they shall go out and look on the dead bodies of the men who have rebelled against me. For their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh” (Is. 66:24).

This passage is essential to a Jewish worldview of burial because of how it portrays non-burial. Not only that, but being left unburied for the worms to devour would signify one of the more horrific, shameful manners of death. Jesus likewise uses this verse in Mark 9:48 to link the Hinnom Valley to this specific passage. Therefore, we can understand from Jesus’s words that this particular manner of shameful death did, in fact, occur in Jerusalem’s detestable Hinnom Valley (Gehenna).

The Resurrection of the Dead

The most significant reason, however, why a Jew desired a proper burial, besides being remembered honorably, is so the deceased’s body would be preserved and be suitable for a future, bodily resurrection in “that day” as prophesied by various Biblical prophets. One of the more well-known prophecies about this is found in Ezekiel 37 and is generally referred to as the Valley of Dry Bones. In that prophecy, God informs Ezekiel of a future resurrection where bodies will be fused together and live again. Though there are additional explanations for this passage, such as the bodies representing the nation of Israel coming back together after the exile, a more familiar one from ancient times was that the individual people of God would rise and live again. In other words, each Jew will be raised in a bodily manner. This is not the same as what contemporary Christians consider “heaven” to be like, but it is instead a future, bodily resurrection at the end of time to be with Yahweh in His household.

Other Resurrection Prophecies

Ezekiel 37, however, is not the only passage that alludes to a future resurrection. There are several others from the OT, such as Isaiah 26:19, which states, “But your dead will live, Lord; their bodies will rise—let those who dwell in the dust wake up and shout for joy—your dew is like the dew of the morning; the earth will give birth to her dead.” Psalm 49:15 also appears to explain a future resurrection when the Psalmist writes, “But God will redeem me from the realm of the dead; he will surely take me to himself.” However, the single, most explicit passage from the OT that assumes a future bodily resurrection is Daniel 12:2, where the prophet declares, “Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt.”

Resurrection in Daniel

This prophecy from Daniel is dated by most scholars to about 165 BCE. It is, therefore, not difficult to see how the doctrine of a future resurrection is developing and expanding from the time of the Psalms and Isaiah, to Ezekiel’s Valley of Dry Bones, and then finally to the prophecy in Daniel, which has a significant influence on the New Testament’s idea of resurrection. That verse from Daniel is likewise the most pertinent concerning the manner of death because of how it contrasts “everlasting life” to “everlasting contempt” and not an “everlasting torment.” Those who rise to everlasting life are commonly understood from this verse as only Jews because 12:1 states, “But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone whose name shall be found written in the book.” Ancient Israelites generally believed it was only the Jewish nationals, those who were born Jewish or who converted to the Jewish religion, who ought to be able to spend eternity with God.

To Daniel, everlasting contempt is contrary to everlasting life. Since there was no complete and developed doctrine of the afterlife in ancient Judaism at that time, especially for the wicked, this verse expresses how a person will be remembered after they die. Again, to a Jew, that is significant because of the honor and shame culture where they reside. Being remembered shamefully, in some instances, can be perceived as worse than death for many because your name lives on after you. Therefore, to be remembered shamefully in a culture such as Judaism is a substantial punishment and a fate that everyone wants to avoid.

Death by Fire

In ancient Judaism, one of the most horrific manners that one can die was by having their body burned and consumed in cremation. Being cremated indicates that they will not be with God when the resurrection happens because their bodies will be nothing but ashes. As a result, they cannot participate in the future resurrection. Accordingly, there are very few instances of cremation in the Bible. The only significant act of burning a body is the aforementioned 1 Samuel 31:11-13, when the Israelites discover Saul’s body following his suicide and after the Philistines mutilated his corpse. Though the Bible says they burned his and his son’s bodies, the author immediately afterward states, “And they took their bones and buried them under the tamarisk tree in Jabesh and fasted seven days.” That act of burying nevertheless denotes an honorable death even though their bodies were cremated because the Israelites devoted time to bury their bones and fast afterwards, which is typical in the standard cultural act of mourning. Though Saul had many, many errors during his reign, he is still allowed an honorable burial and subsequently may yet be available for resurrection.

That, however, is the exception. Though cremation is not discussed much in Scripture, we know how Jews felt about it from various other sources. In fact, many contemporary Jews (and some Christians) are still wrestling with the thought of modern cremation, even though there is nothing expressly prohibiting devout religious people from cremating the dead. But it does demonstrate how complex this issue is for some to cremate their loved ones, even today.

Cremation from the Talmud and Mishnah

Most of our understanding of anti-cremation regulations derives from the Jewish works entitled The Talmud and The Mishnah. These books of Jewish law state that the deceased’s body needs to be buried because the soul will gradually rise out of its body and into the spiritual realm (apparently, this may be why Jewish law prohibits embalming the dead like the Egyptians. Similarly, it may be why Joseph was never embalmed in Egypt and instead had the Jews carry his bones with them). To cremate a body is analogous to disposing of the body too fast and not allowing the soul enough time to escape. “Burial is not for the sake of the living, but rather for the dead” (Sanhedrin 47a).

What is fascinating is that Jewish tradition believes there is one bone that never decays, which is located in the back of the neck. This is called a luz bone. It is thought that from this bone, the human resurrection will occur. However, if that bone is destroyed, as it would be in a cremation process, then the resurrection process is obstructed. Therefore, the Talmud states that the individual who is cremated does not have the luz bone intact and does not merit the resurrection.

Cremation in the Hinnom Valley

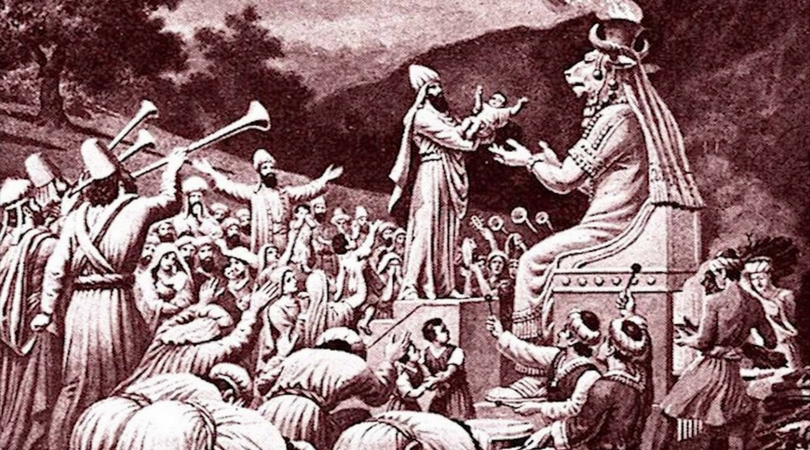

Besides the burning of Saul’s body, the only time Scripture mentions burning bodies is through the sacrifice of children in the Hinnom Valley. However, did cremation genuinely occur in the Hinnom Valley? Archaeology confirms that it did. The late Dr. Eilat Mazar, the famous and renowned Biblical archaeologist, has participated in excavations in the valley and uncovered evidence suggesting cremation, indeed, transpired in that place. If you have not yet read my blog post about sacrifices in the Hinnom Valley, it is listed HERE. The article copy and pasted below will only make sense if you have read that or already understand the language challenges relating to Molek (or a molk offering). In 1993, the AP had a small write-up about this discovery. It is listed here, unedited:

JERUSALEM (AP) _ The valley of Gehenna, which became synonymous with Hell because children were believed to have been burned in sacrifice there, may only have been the site of a crematorium, an archaeologist said Monday.

The valley that plunges from the western side of Jerusalem’s walled city ″has been maligned,″ Eilat Mazar told The Associated Press.

The name Gehenna derives from Geh Ben Hinnom, a place where the prophet Jeremiah said the children of Judah ″burn their sons and daughters in the fire″ (Jeremiah 7:31).

That phrase led many to believe the children were being sacrificed to Moloch, the Phoenician god of fire; other Biblical writers equated the valley with hell.

But findings uncovered at an ancient Phoenician settlement at Ahziv, in northern Israel, indicate that Jeremiah was misread and that Gehenna was a crematorium, Mazar said.

″The crucible we uncovered in Ahziv last year is the closest thing to date to the crucible (in Gehenna) described by Jeremiah,″ she said. ″And bones uncovered nearby indicate a crematorium, not a sacrificial altar.″

Nevertheless, Gehenna would still have been a terrible place for Jews, who reject cremation because of Ezekiel’s prophecy that the dry bones of dead Jews shall rise upon the coming of the messiah.

Mazar’s dig was sponsored by the Jerusalem Bible Lands Museum and Hebrew University. The artifacts she discovered are on exhibit at the museum.

This is a very significant article because it verifies the language concerns and potential reality (or non-reality) of a god named Molek. Similarly, there may have never been child sacrifices to Molek that occurred in the Hinnom Valley, which archaeology appears to, at least for now, confirm. Dr. Mazar says that excavations inform us that a crematorium is present in the Hinnom Valley and not a sacrificial altar. So, what do we make of the Biblical account?

Cremation in the Bible

The Bible does not speak about cremating dead bodies, except to mention how loathsome it is. However, we do have archaeological evidence that cremation did, in fact, occur in the Hinnom Valley. From reading other scholarly journal articles, and digging into archaeological papers (pun intended), it does appear that some (though not all) individuals did perform cremation of their loved ones. A Biblical scholar and professor at Princeton Theological Seminary named Elizabeth Bloch-Smith wrote a book called Judahite Burial Practices and Beliefs about the Dead where she postulates that cremation unquestionably occurred in Judah. However, those cremation rituals are associated with the Phoenicians who were in the land at the time cremation took place. It should be noted that the Phoenicians are also known as Canaanites.

Likewise, it is noteworthy because we have hard, physical evidence that the Canaanites, while in Phoenicia, performed child sacrifice and cremation in the 11th-8th century BCE (also referenced in the book above by Elizabeth Bloch-Smith). This perhaps influenced the Israelite Kings Ahaz and Manasseh in Judah to “pass their sons through fire.” Whether those kings sacrificed their children to Molek or cremated them after a natural death is not known (either way, the manner of burning their children’s bodies is still repulsive to a Jew). Though it may or may not have been used for child sacrifice, the Hinnom Valley was indeed used as a crematorium. Suppose you are a law-abiding Jew, living in the first century, and you know the history of this valley and what transpired within it from Canaanite times, as well as what the valley is being used for in the current first century climate as a place to possibly dump ashes and dung from animal sacrifice (discussed in a previous post), and being used as a crematorium. Does that not put into perspective why it was such a threat to have your body thrown into it?

How Jesus Used Gehenna

Jesus warns the disciples, “And if your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and be thrown into Gehenna, where ‘the worms that eat them do not die, and the fire is not quenched” (Mark 9:47-48). Does this verse make more sense after understanding the entire context surrounding the Hinnom Valley? To hear a warning that it is better to cut off an honorable body part than to have your whole body dumped into a shameful, disgraceful valley, which indicates that you are not eligible for a future bodily resurrection, would be a forewarning that would not go unnoticed.

Honor and Shame in Gehenna

In the above verse from Mark, Jesus speaks of bodily mutilation, which is considered extremely shameful in ancient Israel, especially self-mutilation of an honorable body part like the eye. Jesus asserts that self-mutilation of an honorable body part is a better deed than for your whole body to be cremated in the Valley of Hinnom because of the extremely shameful implications that arise when one has their body tossed into this valley. Jesus effectively states that it is better to cut off a highly honorable body part than to have your body burned, cremated, and disgraced by being thrown into the Hinnom Valley because the fate of that death will remain with you, and you will not be remembered in a good way in that honor and shame society. Jesus uses hyperbolic language frequently, and this language makes much more sense in an honor and shame society like first-century Jerusalem than it would in a contemporary setting. Therefore, to read the modern understanding of “hell” into the Gehenna passages appears anachronistic.

Conclusion

I will explain much more of this hyperbolic language from Jesus in my next blog post but for now, I assume the general idea is conveyed well enough. Proper burial in ancient Israel was essential. It is so essential that if one is threatened with a death without a proper burial and being cremated, the implications that a Jew would take from that reference would be immense. And especially death by cremation previously in a place equated with shameful acts of death by fire. The threat or consequence of Gehenna means something profound to a first-century Jew that may get lost in other cultures around the world due to its precise contextual background relating only to Israel and not to any different culture. Therefore, those unfamiliar with first-century Jewish culture and customs may miss what is being implied in the Gehenna sayings.

Jesus uses a literal, geographical location to suggest a dreadful fate of whoever is cast into that place where all those cremations occurred. Regardless of whether these cremations occurred by sacrifice or simply cremation after natural death, the connotation remains the same. It signifies a shameful death with no possible means to future resurrection. It is difficult to imagine Gehenna serving as an example of what hell is reminiscent of, considering that hell implies a never-ending life of torment. In contrast, the real Gehenna implies a shameful destruction, with no possibility of immortality. The concept of an endless hell is backward from what the symbol of the Hinnom Valley indicates.

Is Gehenna hell? Evidence would suggest that no, it does not suggest an underworld where non-Christians end up if they do not believe in Jesus. It is never described as an otherworldly place but always a literal place of physical judgment that only a first-century Jew would comprehend. Walter Balfour, an 18th-century theologian, also suggests it to be a literal location and not a future place of punishment when he writes, “Nor, do we read of persons going down to Gehenna, of the depths of Gehenna, or the lowest Gehenna. Neither do we read of the gates of Gehenna, nor of the pains of Gehenna.” Those descriptors are present for Hades and Tartarus, but never Gehenna itself.

What are your thoughts on this? I realize it may be controversial to many conservative Christians, but does this make sense after reading the past few blog posts? Do you believe Gehenna to indicate hell? Why or why not?

Previous blog post on child sacrifice is found HERE.

Next blog post on the NT using Gehenna is found HERE.

Further Reading:

The Jewish View of Cremation

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3155612.pdf

https://www.thattheworldmayknow.com/burial-practices

https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/510874/jewish/Why-Does-Judaism-Forbid-Cremation.htm