The Underworld of Judaism—Sheol

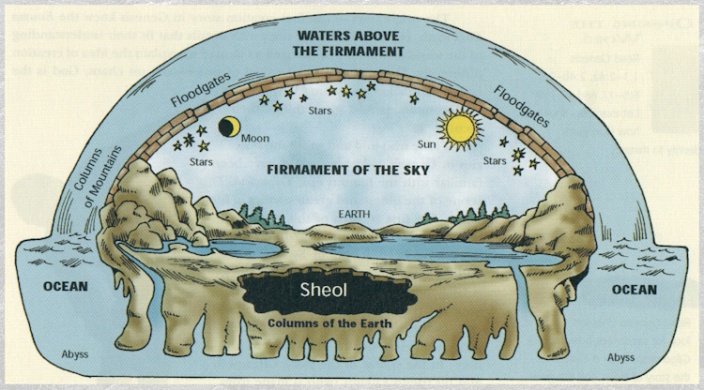

The concept of Sheol representing the land of the dead, as is commonly employed in the OT, is not exclusive compared to other ancient religions. The commonalities are exceedingly similar to that of its counterpart religions in the ancient near east during that time. Sheol is not “hell,” in the traditionalist sense, but is generally described as a dark, dreary place, where all the dead go—both righteous and unrighteous (Ecc. 9:3). It is the fate of all who live and walk the earth no matter how good or bad your deeds were. There is no joy, sorrow, hope, or fear; only nothingness. Much like how many atheists today believe that after you die, there is nothing in the great beyond and no afterlife. That is precisely how Sheol is in the OT.

Origin of Sheol (Etymology)

The etymology of Sheol is uncertain, but there are two possibilities that many scholars support. The first is from the Hebrew sh’h, which describes a barren land—literally meaning “no land” or “unland.” That idea is entirely reasonable when taken in the context of how an Israelite thought of the afterlife, or rather, no afterlife. The other possibility is taken from the Hebrew sh’l meaning “to ask, inquire.” That implication implies communication or consultation with the dead (i.e., necromancy), which is strictly forbidden in OT law. Regardless of which etymological origin one believes, Sheol, as a place, is commonly thought of today as simply a way to express “the grave” or “death.”

To put it in a more modern sense, if someone knows the end of their life is near, they could say something similar to “the grave calls my name,” “I am near to the time of entering the grave,” or even “death calls for me.” These are all literary imageries to suggest death is at hand while personifying or giving a geographical representation of the abstract idea of death. Since most (though certainly not all) references in the Hebrew Bible to Sheol are in poetic form, a specific poetic license should be allowed to the biblical author.

Worse than Death?

In an honor and shame culture like Judaism, however, the notion of not waking up—nonexistence and life permanently lost—inspires disgust, not relief. When most individuals are concerning themselves about life, legacy, and memories, a reality of nothingness is something the people fear. Indeed, leaving a lasting heritage to family and a good reputation means everything to an ancient Israelite. It is why we have verses similar to Daniel 12:2, which states, “Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt.”

Notice how the above verse contrasts “everlasting life” to “everlasting shame and contempt,” and not hell? “Waking up” to your name being forever remembered in a shameful manner and having others think of you in contempt is a serious issue to an ancient Israelite. Their name, which is seemingly all that they have left after they die is at stake, and when they “wake up,” they will be thought of with disgrace and distain, which is a revolting concept to a Jew. Surprisingly, there is much in common between this line of thinking and that of the NT concept Gehenna (blog post, and series, on that topic found HERE).

Separated from God

A related and also dreadful idea comparable to everlasting contempt is that if one goes down to Sheol, God does not even think about them anymore. God is the God of the living, not the dead. Therefore those in Sheol are not thought of any longer by God and are not able to share in the joys of praising God.

However, there occasionally appears to be contradictory statements in the Bible regarding if God can or cannot “go into Sheol.” For example, Psalm 88:5 states, “Forsaken among the dead, like the slain who lie in the grave, whom You remember no more, and they are cut off from your hand. You have put me in the lowest pit (Sheol), in dark places, in the depths.” Likewise, Isaiah 38:18 claims, “For Sheol cannot thank You, death cannot praise You; those who go down to the pit cannot hope for Your faithfulness.”

In contrast, Amos 9:2 God declares to the prophet, “Though they dig into Sheol, from there will My hand take them.” Finally, Psalm 139:8 records the Psalmist speaking to God and saying, “If I ascend to heaven, you are there; if I make my bed in Sheol, behold, You are there.” Therefore, if Sheol is strictly a geographical place in the underworld, such as Hades, then is God there or not? Yet if you notice, these passages (among many, many others) are from the Psalms and prophets who do not necessarily write in a strictly, literalist narrative manner. Some allocation of poetic originality should be understood when reading these passages. The overwhelming consensus is that Sheol is, in fact, the grave.

References are prevalent in the OT about a gloomy, dreary outlook for their eternal state of nothingness in Sheol. Though there are many references to this place in the Hebrew Bible, none cast Sheol in a positive manner.

Sheol is not Hell

The idea of Sheol in the OT is not, in any way, equivalent to our modern understanding of “hell.” All scholars agree (save for a few KJV only people) that there is no punishment in the afterlife according to the Hebrew Bible. Many, in fact, think of Sheol as the OT equivalent of the Greek “Hades,” which is spoken of throughout the New Testament. Most get this understanding from a famous NT quote of an OT Psalm. In Acts 2:27, where Peter is delivering his famous sermon at Pentecost, he quotes a Psalm and says, “For you will not abandon my soul to Hades, or let your Holy One see corruption.” The reference from Peter is taken from Psalm 16:10 which states, “For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption.” They are word-for-word identical except for the NT shifting from Sheol to Hades. There were no other Greek words precisely equivalent to Sheol, so Hades was the chosen as the closest representation of what Sheol was like.

Therefore, many think they are indistinguishable both in nature and thought. The one problem, however, is that Sheol is only a place of the dead while Hades has much more within it’s walls, including Tartarus, the place of punishment. Sheol is thought of as a single compartment, while Hades has multiple compartments and areas, rivers, etc., (simply do an internet search for “hades geography” and you will see what I mean). Whichever way one believes about the NT usage of Hades and if it is similar to Sheol or not, many inevitably lead on to think Sheol is currently perceived the same as the Greek Hades, which, it is the vast majority of the time. However, some Greeks and Jews at the time believed Hades to be slightly different from Sheol. To be sure, there are many similarities, and many thought of them as related in NT times. Nevertheless, they are not always identical in all manners of thought.

Sheol a place or just the grave?

The OT usage of Sheol, however, is fundamentally a technical term for the place where people are buried—”the grave” or “the pit” are the two most common interpretations. Most of the modern English translations reflect that throughout the OT. For example, many Psalms use the art of what is called parallelism to make their point successfully, which is simply a Hebrew poetic device where the two lines of a Psalm are identical in idea but different in words. While English rhymes with sounds, Hebrew “rhymes” with ideas. Psalm 16:10 above is a good example:

For you do not give me up to Sheol

Or let your faithful one see the Pit.

Similarities of Sheol to Grave and Realm of the Dead

Again, poetic license should be allowed to the biblical authors concerning their usage of Sheol and how they sought to express their thoughts of death. An excellent example can be found in the various English translations of one verse in Ezekiel. For example, compare translations of the ESV, NIV, and NLT of Ezekiel 31:17 and their individual choices of how to translate Sheol.

ESV:

They also went down to Sheol with it, to those who are slain by the sword; yes, those who were its arm, who lived under its shadow among the nations.

NIV:

They too, like the great cedar, had gone down to the realm of the dead (Sheol), to those killed by the sword, along with the armed men who lived in its shade among the nations.

NLT:

Its allies, too, were all destroyed and had passed away. They had gone down to the grave (Sheol)—all those nations that had lived in its shade.

There is nothing to suggest that each translation of the Bible thought of the word Sheol differently. They are all the same concept yet written in a distinct poetic manner, indicating a similar line of reasoning. Regardless of how Sheol is translated in the above verses, one thing is quite apparent—Sheol does not equal “hell” in any fashion.

Could Some Believe Sheol be an actual place?

Though many Jews in OT times see Sheol as just a term denoting “the grave”, “the pit,” or simply “death,” there is some evidence that others think it is as an actual place. For instance, the first reference to Sheol in sequential reading of the Bible is found in Genesis 37:35. This is when Jacob was comforted after the supposed loss of his son Joseph and said, “No, I shall go down to Sheol to my son, mourning.” That reference does seem to indicate that Sheol is thought of as an actual place when Genesis was written. However, it could also be a metaphorical reference of someone going “down to the grave.” Regardless of the differing views that people have of Sheol, none of the references in the Bible make it appear like a good place. Instead, it is usually viewed in a negative, and sometimes neutral, light.

A final example likewise comes from Ezekiel when the prophet is foretelling the future demise over Egypt. A slightly lengthy passage but is an excellent expressive display of how the prophet used Sheol.

17 In the twelfth year, on the fifteenth of the month, the word of the Lord came to me, saying, 18 “Son of man, lament for the hordes of Egypt and bring it down, her and the daughters of the mighty nations, to the netherworld, with those who go down to the pit;

19 ‘Whom do you surpass in beauty?

Go down and make your bed with the uncircumcised.’

20 They shall fall in the midst of those who are killed by the sword. She is turned over to the sword; they have dragged her and all her hordes away. 21 The strong among the mighty ones shall speak of him and his helpers from the midst of Sheol: ‘They have gone down, they lie still, the uncircumcised, killed by the sword.’

22 “Assyria is there and all her company; her graves are all around her. All of them killed, fallen by the sword, 23 whose graves are set in the remotest parts of the pit, and her company is all around her grave. All of them killed, fallen by the sword, who spread terror in the land of the living.

24 “Elam is there and all her hordes around her grave; all of them killed, fallen by the sword, who went down uncircumcised to the lower parts of the earth, who inflicted their terror on the land of the living, and bore their disgrace with those who go down to the pit. 25 They have made a bed for her among the slain with all her hordes. Her graves are around it, they are all uncircumcised, killed by the sword (although their terror was inflicted on the land of the living), and they bore their disgrace with those who go down to the pit; they were put in the midst of the slain.

Reading the above passage from Ezekiel is an excellent way to see how the Israelites viewed the underworld of Sheol being a good representation of “death.”

Conclusion

Though Sheol may have some different aspects regarding how it was perceived in ancient Jewish thought, it seems apparent that it was a place and/or metaphor for death. The Jews of OT times believed in death, nonexistence, extinction, and annihilation. Not in a tormented sense or even as punishment, but something that all people experience. This philosophy is similar to many of the surrounding religions of Israel’s day and appears to be the common understanding of what happened to a person after death. It is important to remember as we continue our study into the NT belief in the afterlife, what that entails, and how people saw it during their time. In a future blog series on “the words of hell,” I will give more detail on how Sheol is thought of and used in conjunction with hell, according to some KJV only people.

Final Post on the History of Hell

This is the last blog post on the history of hell. I am sure some of you are glad it is over because there are six long, boring blog posts on this subject. However, I felt it necessary to give a brief overview of what life after death was like before we reach the teachings of Jesus in the Gospels. Having this foundation of the history of hell will help us out tremendously at a later time and during a later blog series.

What has been something you learned from this series? Was there anything surprising to you or anything you disagree with? Let me know, I enjoy discussing this topic extensively!

Previous blog post on Tartarus is found HERE

Next blog post on 3 Burning Questions About Hell is found HERE

Further Reading:

Ehrman, Bart. D. Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Publishing, 2020.

Balfour, Walter. An Inquiry into the Scriptural Words Sheol, Hades, Tartarus, and Gehenna, All Translated Hell, in the Common English Version. Published by Benj. B. Mussey. Scholars Select Series, 183