The Geographical Valley of Hinnom

The Valley of Hinnom (occasionally referred to as The Valley of the Sons of Ben Hinnom) in the Old Testament is a literal, geographical location just beyond the walls of Jerusalem. Jesus uses the Valley of Hinnom (Greek Gehenna) in some of his parables to describe a fate that is rather dreadful. Likewise, Jesus warns the Apostles of this place and threatens the Pharisees with the fate of Gehenna. In order to see how and why Jesus would use this geographical location as an example of a specific manner of fate, it is beneficial to investigate what His view of that valley was by examining what the Bible He used (the OT) reveals concerning its nature. If you have not yet read the Gehenna etymology post, it is located HERE. Reading that post initially will provide a better understanding of the word Gehenna, and then this post will look at the literal place of Gehenna.

A Boundary

The earliest reference of the Hinnom Valley (Gehenna) occurs in the book of Joshua where he is distributing the promised land for the Jews to inhabit. For the boundaries of the tribe of Judah the author writes, “Then it ran up the Valley of Ben Hinnom along the southern slope of the Jebusite city (that is, Jerusalem). From there it climbed to the top of the hill west of the Hinnom Valley at the northern end of the Valley of Rephaim” (Josh. 15:8). Afterwards, for the tribe of Benjamin, the biblical account states, “The boundary went down to the foot of the hill facing the Valley of Ben Hinnom, north of the Valley of Rephaim. It continued down the Hinnom Valley along the southern slope of the Jebusite city and so to En Rogel” (Josh. 18:16).

The final reference of the Hinnom Valley as a particular boundary comes from Nehemiah 11. After the exiles return from captivity they wish to settle back in their homeland. Towards the conclusion of the book of Nehemiah, the author records the location of where all the leaders of Jerusalem resided. The location of residence is recorded for the sons of Benjamin that comprise of the priests, the Levites, the gatekeepers and the overseer of the Levites (Uzzl). After listing the leaders of Benjamin, the author documents where others encamp when he writes, “As for the villages with their fields, some of the people of Judah lived in Kiriath Arba and its surrounding settlements” (11:25). Subsequently, the author then catalogs several places by name and in verse 30 he writes, “So they were living all the way from Beersheba to the Valley of Hinnom.” There is nothing unusual in these verses about the geographical valley itself except that it operates as a border similar to how a valley or river would operate as a border today.

Jeremiah’s Valley of Hinnom

What the valley is primarily notable for, however, is derived from the writings of Jeremiah. The first mention of the valley by the prophet is when God divulges to the prophet Jeremiah concerning the people of Judah, “They have built the high places of Topheth in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to burn their sons and daughters in the fire—something I did not command, nor did it enter my mind. 32 So beware, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when people will no longer call it Topheth or the Valley of Ben Hinnom, but the Valley of Slaughter, for they will bury the dead in Topheth until there is no more room” (Jer. 7:31-32). It appears the valley is being utilized prior to the siege of Jerusalem by the Babylonians to offer child sacrifices by fire, something considered an abomination to the Lord.

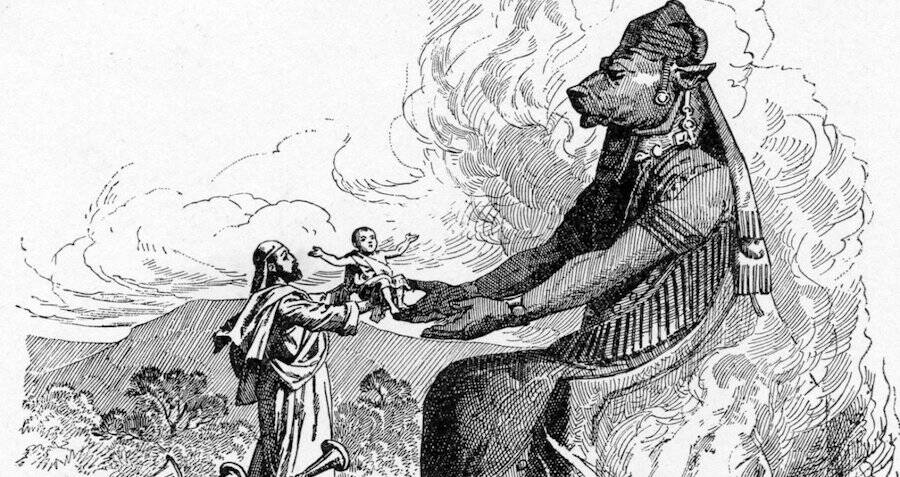

A very similar prophecy is in Jeremiah 32:35 when God likewise declares, “They built high places for Baal in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to sacrifice their sons and daughters to Molek, though I never commanded—nor did it enter my mind—that they should do such a detestable thing and so make Judah sin.” Though similar to the previous verses, this verse specifically names two gods: Baal and Molek. The Bible makes it evident, in many other passages likewise, that the people of Judah were constantly worshipping foreign gods. Not merely worshipping, but worshipping through the abominable practice of child sacrifice to the god Molek (this will be the subject a blog post shortly). The common understanding of how this practice functioned is that there was an idol with the head of a bull and the body of a man with his arms outstretched. That is where the parents would place the child to be sacrificed. They would then light a fire underneath, by the idol’s feet, until the child dies and is consumed to ashes.

Child Sacrifice and The Law

Obviously, God does not authorize any of this in any fashion. Not to mention that it is also specifically prohibited in the law when God says to Moses, “Say to the Israelites: ‘Any Israelite or any foreigner residing in Israel who sacrifices any of his children to Molek is to be put to death. The members of the community are to stone him” (Lev. 20:2). Because of this law, God correspondingly uses Jeremiah to prophesy against the people of Judah for this specific practice of child sacrifice when He expresses to the prophet to go out the potsherd gate, which leads to the Hinnom Valley, and proclaim to the people:

“Hear the word of the Lord, you kings of Judah and people of Jerusalem. This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: Listen! I am going to bring a disaster on this place that will make the ears of everyone who hears of it tingle. 4 For they have forsaken me and made this a place of foreign gods; they have burned incense in it to gods that neither they nor their ancestors nor the kings of Judah ever knew, and they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent. 5 They have built the high places of Baal to burn their children in the fire as offerings to Baal—something I did not command or mention, nor did it enter my mind” (Jer. 19:3-5).

The Folly of Manasseh

According to 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles, the Judahite kings Ahaz and Manasseh are the ones who are largely responsible for sacrificing their children in worship to the god Molek. Their apostasy (especially Manasseh’s) is what leads directly to Judah’s downfall. Though perhaps not the child sacrifice specifically (however it may perhaps be the leading cause) God declares in 2 Kings 21 that Manasseh is the main reason that the people being exiled when he says, “Manasseh king of Judah has committed these detestable sins. He has done more evil than the Amorites who preceded him and has led Judah into sin with his idols. 12 Therefore this is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: I am going to bring such disaster on Jerusalem and Judah that the ears of everyone who hears of it will tingle” (2 Kings 21:11-12). The word in verse 12 “therefore” links the siege of Jerusalem specifically to Manasseh’s evil and wicked acts. Though he is not the sole purpose of why the exile occurs, it appears to be the last straw according to Yahweh and now His people must pay for their wickedness.

Soon after the reign of Manasseh and Ahaz, the great king Josiah appears and causes Judah to repent and yet again follow Yahweh. He rediscovers the book of the Law (which most scholars identify as Deuteronomy) and tears down the high places of worship to Baal and desecrates Topheth in the Hinnom Valley, where the sacrifices occurred, so that the people can no longer go to that location. God is obviously satisfied with Josiah’s reforms and assures the king that he will not see the disaster that is coming to the city. Though, it is too late at this point to save all Judah from being exiled, it is uncomplicated to see the reputation that the valley is achieving by the atrocities that occurred within it.

The Garbage Dump

One of the more controversial aspects of the Hinnom Valley, however, amongst many who research and investigate this topic is that the valley was treated as a garbage dump where the fire was kept burning continuously. The garbage dump theory was popularized by Rob Bell in his book Love Wins but is repeated nonetheless by countless other authors, both before and after him. This theory originates from a rabbi named Kimchi (also referred to as Kimhi) in the 13th century CE. In his commentary on Psalm 27, the rabbi writes, “Gehenna is a repugnant place, into which filth and cadavers are thrown, and in which fires perpetually burn in order to consume the filth and bones; on which account, by analogy, the judgement of the wicked is called ‘Gehenna’” The problem that countless individuals have with this account is that there are currently no supplementary writings extant prior to this that speak of a garbage dump occurring in the Hinnom Valley. Likewise, there is no archaeological evidence that indicates this valley being treated in that manner. Although, archaeologists have unearthed a garbage dump in the Kidron Valley, which is connected in the south to the Hinnom Valley.

Dung Gate

There is, however, circumstantial evidence that may in fact suggest there was a garbage dump being employed in the Hinnom Valley. In Jeremiah 19:2, the prophet goes out of the Potsherd Gate, which opens into the Hinnom Valley. According to the Aramaic Targums, the Potsherd Gate is also known as the Dung Gate, which in Hebrew is called Sha’ar Ha’ashpot, that literally means the “gate of garbage.” Likewise, the Potsherd Gate refers to garbage as well because Potsherd indicates a broken piece of pottery, usually found in excavation sites. If there was no garbage dump in the Hinnom Valley, why did the “Garbage Gate” open directly into the valley itself?

Animal Waste

Some, however, may also believe that this gate is the location where animal excrement was taken to be discarded since animals were prevalent within the city walls to be used both for sacrifices and for food. If hundreds of animals were within the city, and since Jews were infamous for their cleanliness, then what did they do with all the animal dung that was certainly widespread in the city?

Likewise, the Law in Leviticus states about sin offerings that after a sacrifice is made, and the animal is consumed and brought to ashes, they are to be dumped “outside the camp…to the ash heap” (Lev. 4:12). Comparably, the law also states in Exodus “But the flesh of the bull and its skin and its dung you shall burn with fire outside the camp; it is a sin offering” (Ex. 29:14). The relation is simple to see; the priests take the animal dung and flesh and burn it outside the camp while the ashes from the sacrifices are to be discarded there as well. The gate where the priests brought these items was most assuredly the dung gate. Why name it the dung (or garbage) gate if it has no bearing on the gate whatsoever? It does seem clear that the gate was used in some fashion to dispose of something unclean.

Dead Bodies in the Valley

God additionally prophecies later in Jeremiah that restoration of the city will eventually occur, and that it will also encompass, “The whole valley where dead bodies and ashes are thrown” (Jer. 31:40). There are a few theories concerning whose bodies are being addressed. There is the obvious reference above to animals’ bodies as some commentators believe because it is paired with “ashes” and are not seen as human ashes, but ashes from the sacrifices. Others imagine this is alluding to dead bodies of executed criminals that are discarded and left unburied, though, this does appear only to be conjecture at this point since we currently have no extant writings or archeological evidence to suggest that is indeed the case.

Jewish Burial Practices

One aspect of Judaism that is not considered very often is how and why the Jews were so concerned with proper burial practices. Burial practices were essential not just to the Jew, though, but for all in Mesopotamia. In fact, one of the more general curses we see in ancient Mesopotamian texts is, “May the earth not receive your corpses,” or something incredibly similar. In Israel, however, if someone is not buried properly, they would not be eligible for the resurrection on “that day.” One of the methods that displays the importance of the act of burial is in the apocryphal text of Tobit. In this text, the protagonist, Tobit, is among those Jews who are exiled to Assyria. The text states of Tobit:

16 In the days of Shalmaneser[a] I performed many acts of charity to my kindred, those of my tribe. 17 I would give my food to the hungry and my clothing to the naked; and if I saw the dead body of any of my people thrown out behind the wall of Nineveh, I would bury it. 18 I also buried any whom King Sennacherib put to death when he came fleeing from Judea in those days of judgment that the king of heaven executed upon him because of his blasphemies. For in his anger he put to death many Israelites; but I would secretly remove the bodies and bury them. So when Sennacherib looked for them he could not find them” (Tobit 1:16-18).

What this text demonstrates, regardless of its dependability as an accurate historical account, is how essential it is for the Jew to be buried. Even though the narrative is not necessarily “true” in the modern sense, we can still gather essential contextual information from the story.

Importance of Burial

Burial is vital so that the Jew will eventually be resurrected “in that day,” as Scripture states, to be with God. Therefore, the force of the curse referenced above of “may the earth not receive your corpses” becomes more noticeable. It is an extreme offence to wish non-burial to anyone. If there is no burial, there is no resurrection with God. As a result, the Jews were concerned with precisely how someone died. If an individual was left unburied to rot, be eaten by animals, or drowned in the sea, they would inevitably not be able to be resurrected in that day with God.

Shameful Ways to Die

That insight does make other stories in the Bible slightly more apparent in context as to its implications. One example is when Elisha is threatened by a crowd of 42 young men in 2 Kings 2. In that story, the young men are threatening Elisha, so he calls down a curse and the young men are mauled and killed by two bears. Dying this way would render the deceased unable to participate in the resurrection so the curse is even more profound than just dying because it implies a permanent death with no hope of future resurrection.

Likewise, Jonah and the big fish is a parable that expresses a wonderful narrative of repentance for a lost and rebellious people. However, for the Jew in that day, the threat of not only drowning but being eaten by an animal has a massive effect on the hearer because of how Jonah willingly threw himself overboard and subsequently was swallowed by a great fish. For the Jew hearing this story, the manner in which Jonah chose to be thrown overboard, and then be swallowed by an animal (whether he knew that would happen or not) has a dual purpose to its approach and has great hyperbole about the importance of following God’s commands, especially for a prophet. That story has significant cultural ramifications.

Summary

The essence of this valley should be stronger due to its cultural context. It is a valley where abhorrent child sacrifices were performed, dead bodies of possibly human or animal origins (but dead bodies nonetheless) are disposed, ashes from sacrifices are thrown in, and perhaps garbage was discarded or burned here as well. This valley does not have a good reputation. Consequently, if someone were to threaten a Jew that they could be “thrown into the Valley of Hinnom,” that would mean something serious to them. Not only would that fate mean death, but death in an exceptionally shameful manner and a manner that would equate the individual with what was reserved for residue of sacrifices, dung, and enemies of the Jewish people. The Jew would perish in an unclean place, where repulsive practices were performed rendering them unclean and leaving a lasting legacy of shame due to their manner of death. It would also indicate no resurrection for that person because of a lack of proper burial. Therefore, a fate of death in the Valley of Hinnom would be the worst possible fate a Jew could potentially endure.

Conclusion

Realizing the background of the geographical Valley of Hinnom can inform someone on exactly how to view this valley and exactly how it is used in reference to the Jews in NT times. When Gehenna is employed by Jesus, the cultural background of this valley must come with the reference. Understanding what the OT first says about the valley will help the interpreter understand the NT references much better because the context of the Gehenna sayings of Jesus will become clearer once the proper context is revealed.

What are your thoughts on this? Was any information new to you? Does the threat of the Valley of Hinnom mean more to you now?

Further Reading:

Papaioannou, Kim. The Geography of Hell in the Teachings of Jesus. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2013.

Bernstein, Alan E. The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Publishing, 1993.

https://www.biblestudytools.com/dictionary/dung-dung-gate/

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ancient-burial-practices